January 29, 2022

Bankhead, Alberta: A Cursed History of a Ghost Town

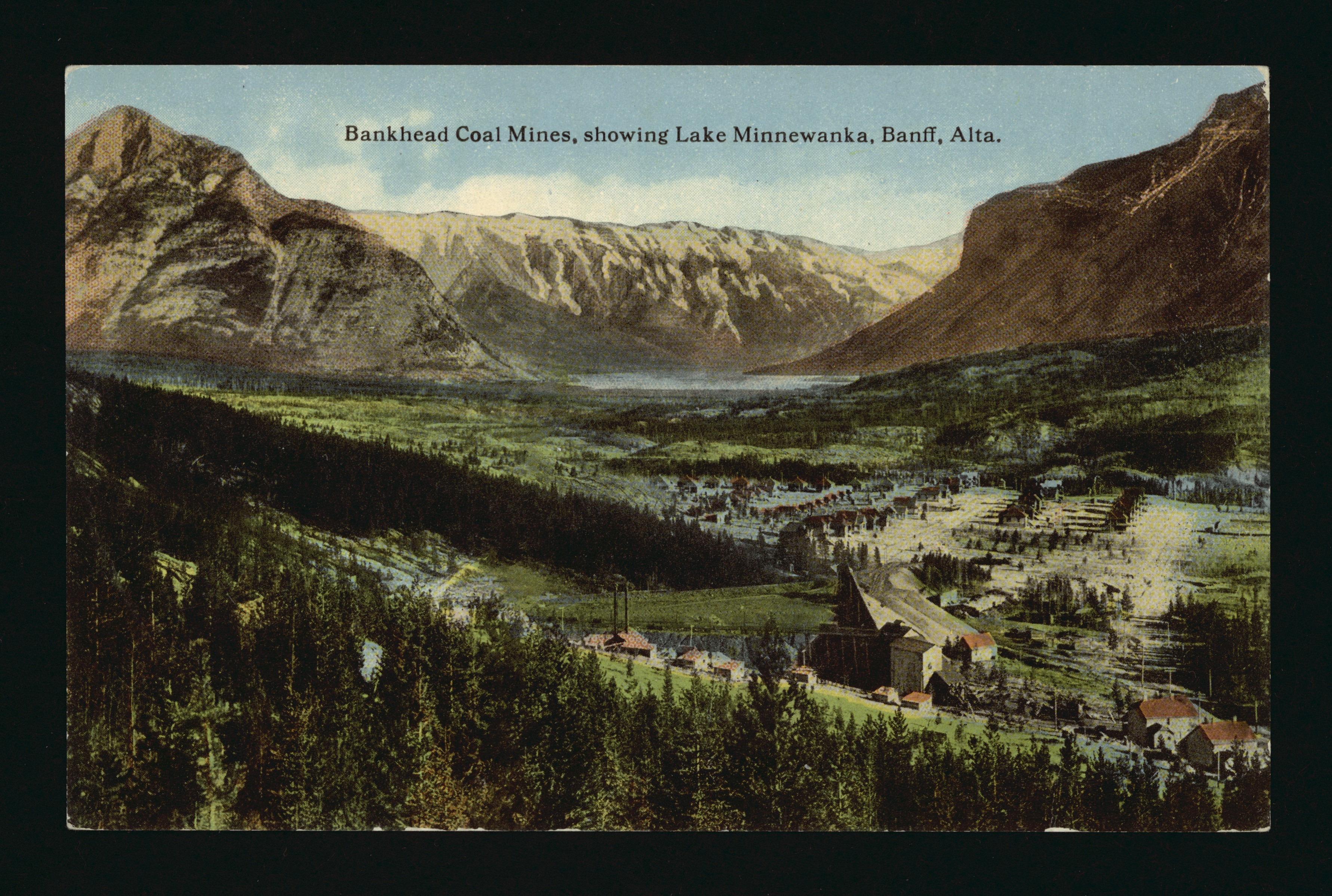

An easy excursion from Canmore is the historic ghost town of Bankhead, an abandoned coal mining town near Banff.

The Canadian Pacific Railway established Bankhead Mine in 1903 at the foot of Cascade Mountain. Bankhead grew quickly and its population eventually reached 900 – larger than Banff at the time. Bankhead ‘was a forward-looking, thoroughly modern community. Bankhead’s power plant produced all the electricity needed for the mine and town, and enough to supply the town of Banff as well. At the peak of Bankhead’s prosperity, nearly 300 men worked underground and another 150 labored above-ground. Coal production reached nearly 200,000 tons a year,’ Parks Canada explains.

Bankhead was a multicultural town whose residents came from a wide range of cultures – there were Polish, Italian, British, Russian, German, Irish, Czechoslovakian, American, and Francophone families, recounts author Ben Gadd in his book, Bankhead: The Twenty Year Town.

There were also 60 Chinese workers, brought to Canada to sort coal from rock at low wages. ‘The Chinese kept (or were kept) apart in every respect,’ Gadd writes. ‘Each morning the Chinese walked in single-file to their dirty jobs in the tipple. In the afternoon they returned to their shacks …without the benefit of the company wash-house. Somehow, in those drafty shanties, they kept warm and clean.’

‘The few children who were allowed to visit (or did so on the sly) found the Chinese to be quite likeable. They presented the children with small gifts: Chinese litchee nuts, paper flowers, and – oh, boy – firecrackers! The First New Year’s blowout behind the slack piles took the town by surprise. After that, the event always drew a crowd.’ – Bankhead: The Twenty Year Town

The bilingual Chinese boss, known to the townspeople as Slippy (his real name was Chow Hee), was the main communicator between the Chinese workers and the heads of the company. Chow Hee’s wife and family lived with him in Bankhead for some time. (This is in contrast to most Chinese workers, who left their wives behind in China while they toiled in Canada to earn money to send home.

At one time, Bankhead was a bustling mining town, bigger and more modern than Banff. The mine workers included Chinese laborers, who endured systemic discrimination from the government and from mainstream society. Under the Chinese Immigration Act, the Canadian government required every Chinese worker and family member to pay a head tax to enter Canada (from $50 per person in 1885, and raised to $500 per person, from 1903 to 1923 – when the federal government put an end to Chinese immigration to Canada with the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act). The federal government did not require immigrants from any other country to pay a head tax to come to Canada. Because of the head tax, an enormous sum of money in those days, most early Chinese immigrants were men, who came to Canada to work.

Chow Hee, foreman at Bankhead and the main communicator between the Chinese workers and the heads of the company, was fortunate enough to have a family in Canada. Pictured from left are three of his children: Louise, Charlie and Lorna, 1925. Largely due to the systemic racism at the time, Mrs. Chow left Canada and returned to China, taking the children with her, while Mr. Chow remained in Canada. The family was reunited in Canada decades later. The Canadian government repealed the Chinese Immigration Act in 1947. Learn more about Canada’s early Chinese immigrants

Read more about Chow Hee’s Family, The Dark Side of the Mountain

An unstable coal market, high costs, the discovery of less expensive, higher quality coal sources, and labour strife eventually led to the mine’s closure in 1922. The buildings were removed, and many of them were taken to Canmore and Banff. The town of Bankhead ceased to exist in 1925.

Today, Bankhead lives on as a ghost town. Jordan Ede is lead guide and instructor with Mahikan Trails, an Indigenous-owned company sharing teachings from the land through snowshoeing, medicine walks and canyon walks into Grotto Canyon near Canmore.

Ede, an interpretive guide certified through the Interpretive Guides’ Association, tells the unusual story of the Bankhead cemetery.

Whenever there was a fatality at the mine, the funeral and burial took place in nearby Banff, since Bankhead had no cemetery of its own.

“Bankhead residents felt that if they lost a fellow worker or friend, they had the right to have a wake. They would get as drunk as humanly possible in remembrance of the person who was lost. Residents of Banff didn’t really like this – they were sick of walking by these people passed out in the gutter,” Ede says.

The First Curse of Bankhead

Eventually, a cemetery was commissioned in Bankhead– but there was a hitch. Many of the workers in Bankhead had immigrated from Scotland and China –distant corners of the Earth with cultures that were incredibly different. But something they had in common was a superstition that being the first person to be buried in a new cemetery would put a curse on their family: that the entire family would soon follow the deceased into the afterlife, Ede explains. As a result, no one was actually buried in the Bankhead cemetery for some time. And as it turns out, only two bodies were ever buried at Bankhead; today, only one remains…

The first to be buried, in 1921, was a Chinese worker. The Bankhead residents reasoned that since the deceased worker’s family was so far away, in China, the curse was unlikely to affect them. However, when his family found out, several years later, that he had died, they arranged to have his remains returned to China.

The other burial was the town’s stray dog. “Everybody adored the dog, and it didn’t belong to anybody. They figured that if they buried the dog, the curse would end. And the only body still remaining in Bankhead’s cemetery is that dog,” Ede says.

The Second Curse of Bankhead

Calgary, Alberta-based author and photographer Don Beers recounts the story this way, in his hiking guidebook, Banff-Assiniboine: A Beautiful World: ‘Chinese workers were hired to sort coal at the tipple. Dan McCowan writes that in 1921 the body of a Chinese worker, Yee Chow, was found near a snowbank in the big avalanche slope above town. Apparently he had been searching the slope for herbs, and was killed in a snowslide …

‘Before his death, Yee Chow visited the elderly town laundryman, Sam Sing …. Sing was accused of murdering Yee Chow. For lack of evidence, he was acquitted, but in response to pressure from suspicious townsfolk, Sam Sing was deported. Someone started a rumour that he laid a curse on Bankhead when he left town, and that this is why the mine closed down a few weeks later, making Bankhead a ghost town.’

Hiking Bankhead

Bankhead is best visited in late spring through summer and fall.

There is a 1.1-km interpretive loop around Lower Bankhead.

“You get to see an interesting piece of local history, without the crowds,” Ede says.

To reach Bankhead, turn off the Trans-Canada Highway at the Banff east interchange onto Lake Minnewanka Road, 3.1 km to the Lower Bankhead parking lot.

The hike to C Level Cirque starts from the Upper Bankhead Day Use area on the Lake Minnewanka Road, 3.5 km north of the Trans-Canada Highway. On this hike, you’ll pass by open vent shafts from the abandoned Bankhead mine. The trail climbs steadily, then steepens as you approach the cirque. The superb views are well worth the effort. (430metres in elevation gain, 3.9 km one way). Check the Parks Canada Banff trail report for up-to-date conditions, before you go. C Level Cirque was named for C Level seam, the highest coal seam mined at Bankhead.

Resources:

Bankhead: The Twenty Year Town, by Ben Gadd. Published by The Friends of Banff National Park, in cooperation with Canadian Parks Service, Banff National Park

https://archive.org/details/PC014590

Banff-Assiniboine: A Beautiful World, by Don Beers https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/9108712-banff-assiniboine