February 26, 2021

The Dark Side of The Mountain, The History of Ha Ling Peak

By Jacqueline Louie

One of the most popular ways to explore the Canmore area is on foot. Canmore offers a wide variety of hikes – from serene forest walks, to breath-taking viewpoints of the Bow Valley. One of the Bow Valley’s most iconic hikes, Ha Ling Peak, has a distinctive history that harkens back to Canmore’s mining past.

Ha Ling Peak

Ha Ling Peak is named after the man recorded as being the first to climb it: a Chinese immigrant, Ha Ling, who made his ascent in October 1896. The story most often told, is there was a bet made about who could climb the peak first. “The Chinese guy does it in five or six hours. Ha Ling, the Chinese guy, passes the white guy on the way down. The white guy doesn’t believe him, and the next day a group departs from Canmore, climbs to the top and finds Ha Ling’s handkerchief in a cairn he made on the summit.” In another version of the story: “He climbs the peak and nobody believes him. So he goes up there a second time and this time, they give him a big red flag and he waves the red flag from the summit.”

From that point on – for more than 100 years – the mountain was called Chinaman’s Peak.

According to the Medicine Hat News, reporting on Oct. 22, 1896, Ha Ling, a Chinese cook for a Canmore mining company, climbed the peak as part of a $50 bet that he couldn’t climb it and be back in town within 10 hours. In those days, $50 was an enormous sum – it would have been the equivalent of a year’s wage for a worker of Asian descent, notes Roger Mah Poy, a retired teacher who lived in Canmore for 20 years.

In the 1960s, Banff’s Jon Whyte – author, broadcaster, publisher, local historian and museum curator – had suggested changing the mountain’s name. But it was not until the mid-1990s that things actually moved forward. Mah Poy was part of a small group of Albertans who helped change the narrative and the public’s understanding of why ‘Chinaman’ was a racist term and that Ha Ling’s name should be attached to the mountain.

“We helped to have the community realize that in order to honour all Chinese, it would be better to use his given name, rather than a racial slur. It’s a happy story in the sense that Ha Ling was successful. It’s a sad story in that almost 100 years passed by and the story was almost lost,” Mah Poy says.

The Medicine Hat News story suggested the mountain should be named for Ha Ling, for his daring intrepidity in climbing it. A century later, when Mah Poy and others read the article, they wondered why the mountain did not bear his name. “Largely, it was a situation of cultural misunderstanding and in some ways racism that it didn’t have Ha Ling’s name, because they didn’t know at the time that that was his name,” Mah Poy says.

“In 1997, we ran into a lot of people who said the name ‘Chinaman’s Peak’ honoured all the Chinese people of the valley. At one time, there was quite a large Chinese population that used to live on the side of the mountain that was considered mine side. It was literally the side of the mine where the Chinese used to live. It was a pretty rugged, rough, humble existence and a very subsistence kind of thing. The Chinese were always a part of the community, but they were very separate communities: mine side versus town side.”

At that time, many Chinese workers were employed as cooks, laundry workers and general laborers. In those days, they were all nameless people.

“The Chinese were not known by their given names, only by their ethnicity,” Mah Poy explains.

Some of the old mining books listed their Chinese workers as ‘Chinaman 1, 2, 3’ – “so the racism is real, and it’s in two parts. It’s a denial of personhood, because you don’t know the person’s name, you just know their ethnicity. And the term ‘Chinaman’ is a derogatory slur. It isn’t just a descriptor of an ethnicity.”

The Alberta Geographical Naming Board changed the mountain’s name in July 1997. The renaming – an approximately six-month process, with hearings taking place in Canmore and Calgary – is highlighted in a CBC documentary, Ha Ling Peak.

“To have a mountain named for somebody of Chinese descent is remarkable, because there are so many other mountains where a person’s name is attached to it, but they have no actual connection to it. That’s the reason we were fighting so hard (to change the name). A lot of people would say we wanted to change history. But we didn’t want to change history, we wanted to preserve history the way it should have been right from the start,” Mah Poy says. “This is an important piece of Canadian history – it’s a landmark named after a Chinese guy. This is one of the only, if not the only, peak in Canada named after a Chinese climber.”

The Stoney Nakoda also have a name for this mountain – the Ehagy Nakoda Range. Ha Ling Peak is Ehagy Nakoda’s westernmost summit, overlooking Canmore from the south.

“People used to go partway up and have visions up there and have a look around. There are pictographs – obviously, humans have been going up there for thousands of years. I would guess that perhaps they had conversations with the Chinese and said there is a way up there,” Mah Poy says.

Jerry Auld, a Canmore author, animator, cultural historian and climber, has also thought deeply about Ha Ling’s story.

“He had a name, a culture and a whole story behind him,” says Auld, who wrote a series of short stories about first ascents in the Bow Valley for Gripped Magazine. He thinks there may be another, far more plausible reason behind Ha Ling’s ascent of this mountain beyond the commonly told story of the bet.

At that time, Auld notes, Chinese workers in Canada were not even treated like second-class citizens, but rather like cattle. Their employers typically didn’t refer to them by name, only by number. This was partly due to the fact that “this is very much a story about a white male perspective in the Victorian era,” Auld explains. “They couldn’t pronounce Chinese names or write them down, so they just gave them a number. These people were not important to them – they were just cheap labour.”

The CPR hired large numbers of Chinese laborers coast to coast. The Chinese were incredibly valued workers because they were so diligent and hardworking, and were usually given the most dangerous jobs. Yet workers of other nationalities would receive up to double the amount the Chinese were paid.

Hobart McNeill, mine owner, manager and head of the board for the Canmore mining company wrote circa 1898: “They (Chinese workers) are by odds the best, besides being the cheapest, and candor compels me to say they would be the best at any price,” as noted in The History of Canmore, by Rob Alexander.

“These two cultures did not intermix. In some cases, the Chinese were not allowed into the hotels, drinking establishments or even grocery stores. There was no way they were going to be drinking in the same bar having bets,” Auld notes. Not to mention that “$50 back then was a massive amount of money.”

Auld thinks that Ha Ling climbed his mountain, not on a Sunday, the traditional day of rest in Canada and the West – but rather on a Thursday.

“Why would he be climbing a mountain on a Thursday? To me, that makes no sense.”

Puzzling over this, Auld turned from the Gregorian calendar, to the Chinese lunar calendar. He found that according to the Chinese calendar, the date that Ha Ling climbed the mountain was highly significant: it was the ninth day of the ninth lunar month, known as ‘Double Yang.’ “Nine is a really important number in Chinese culture. It’s considered to be very ‘yang’ or masculine – a day of enormous male energy.”

The Double Yang Festival, also known as the Double Ninth Festival, or Chongyang Festival, is widely celebrated in southern China, specifically in the Cantonese-speaking regions, where the vast majority of the early Chinese immigrants to Canada came from. According to mythology, a monster was killing people – and a hero climbed a mountain, then fought and slew the monster. In another interpretation, people also went to the mountains to honour their ancestors. Climbing mountains has been a Chinese cultural tradition for thousands of years, and is associated with long life and vibrant health.

Auld believes this Chinese cultural tradition was the impetus for Ha Ling to climb his mountain. “It wasn’t because of a bet or a boast in a bar, it was because of this festival the Chinese were celebrating, and Ha Ling was off to honour it by climbing a mountain.

“There was a very rich Chinese culture here in the valley, with traditions that had come from China. For white guys, climbing wasn’t really the sport of the day.” On Sundays, the average miner or logger would rest or go fishing or hunting, Auld explains. It wasn’t until the CPR started to bring in Swiss guides, build hotels and advertise climbing mountains, that climbing became popular in the Canadian Rockies.

No one seems to know what happened to Ha Ling after his historic climb was reported by the Medicine Hat News. But thanks to Mah Poy and all the others who supported changing the mountain’s name to honour him, Ha Ling will remain an important part of Canmore, and Canadian, history.

Ha Ling was typical of the early Chinese immigrants to Canada, Mah Poy says, “who lived by their curiosity, intelligence and courage to beat expectations.”

Mah Poy adds: “All immigrants, regardless of where they came from, they gambled it all, just to come to Canada. They endured terrible travels on the ocean, they didn’t know the language, and in the case of the Chinese, they endured incredible persecution. So I really admire the courage of all immigrants.”

Mah Poy describes Canmore and the Bow Valley as “such a cosmopolitan place – the mountains drew people from all over the world. To be an immigrant, to come to Canada where you don’t know the language, you don’t know the food, you don’t know the customs but you still come – it takes tremendous courage to do something different . . . And that’s why we climb mountains too.”

Ha Ling Peak, which rises 2,408 m above sea level, now has a good trail to the summit, accessible from the Goat Creek Day Use area. It’s best visited in summer and fall. The elevation gain is approximately 700 m. Being prepared, with good footwear, raingear, sweater, sun protection, water and food is important. Check https://www.albertaparks.ca/parks/kananaskis/kananaskis-country/advisories-public-safety/trail-reports/canmore-and-area/ha-ling/ for updates.

Watch CBC documentary on the history of Ha ling Peak on CBC Gem

Bankhead

If you are interested in learning more about the Canadian Rockies’ mining history, historic Bankhead – at one time bigger than Banff, with 360 kms of mine tunnels – is a good destination after the snow melts, from spring through fall. Head to Bankhead – an approximately 15-minute drive from Canmore – for a self-guided tour.

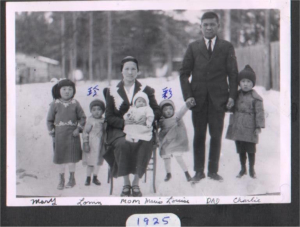

“The current generation knows so little about the price that people before us have paid, that paved the way for us,” says Bea Mah Holland, whose grandfather, Chow Hee, was foreman in Bankhead in the early 1900s, and the main communicator between the Chinese workers and the heads of the company. “We benefited from the persistence of those other generations. The tenacity and the vision of these people is what has really impressed me.”

Ha Ling Mountain Photography by Neil Jolly – Foothills Photographics

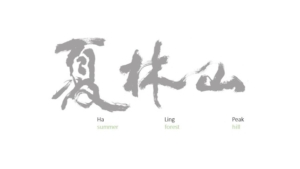

Calligraphy by Kit Au

Story by Jacqueline Louie