April 25, 2021

The Bow Valley’s Trailblazer

A Lawrence Grassi Story

By Jacqueline Louie

Grassi Lakes is one of Canmore’s most popular hikes. It’s a short walk through an open forest of white spruce and lodgepole pine up to two beautiful lakes, with excellent views of Canmore and a glorious waterfall on your way there.

Once called the Twin Lakes, these emerald-hued lakes were renamed for coal miner, mountain guide, park warden, trail builder and Canmore citizen Lawrence Grassi, whose name also graces a Canmore school (Lawrence Grassi Middle School) and a mountain (Mount Lawrence Grassi, a prominent Bow Valley landmark overlooking Canmore from the south).

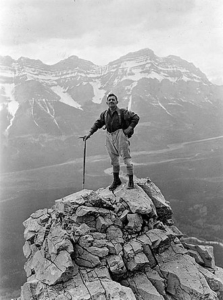

Born in Falmenta in northwestern Italy in 1890, Grassi immigrated to Canada in 1912, settling in Canmore, where he toiled as a coal miner for three decades. During his spare time, he built hiking trails and climbed mountains, with many solo and first ascents. As noted by Chic Scott, author of Pushing the Limits – The Story of Canadian Mountaineering, Grassi’s first ascents include Eisenhower Tower on Castle Mountain, the southeast face of Mount Geikie, and the First Sister above Canmore. Grassi made the first solo ascent of Mount Assiniboine – ‘on a weekend outing from Canmore!’ and climbed Banff’s iconic Mount Louis 32 times. He ‘is reported to have made five guided ascents of Mount Sir Donald in five days at an Alpine Club of Canada camp,’ Scott writes.

Grassi was a highly respected and admired mountain guide. Although he took no payment for guiding, he was as well regarded as the professional Swiss guides brought to Canada by the Canadian Pacific Railway to popularize climbing in the Rockies, note Elio Costa and Gabriele Scardellato in their 2015 book, Lawrence Grassi – From Piedmont to the Rocky Mountains, published by the University of Toronto Press.

After Grassi retired from Canmore Coal Company, at age 65 he took up the post of assistant warden at Lake O’Hara in Yoho National Park, where he lived by the lakeshore in the warden’s cabin for five summers, from 1956-1960. During his time at Lake O’Hara, he built and improved many of the area’s trails. He was a master trail builder – not only a fine craftsman in terms of his technique and skill, but also with an artist’s eye and vision.

Costa, a York University professor emeritus, first learned about Lawrence Grassi on a visit to Western Canada in 2000. “I was intrigued by the importance which this humble miner had for Canmore, Lake O’Hara and the whole area, and the impact he had on the people who met him,” he says.

“My approach to Grassi was really an homage to the life of a man who dedicated his whole life to the mountains. And the people who met him, recognized this and loved him for it. Because it was the most generous approach that any individual could have … and his way of going out with a wheel barrel, pick and shovel and building trails so that average people, and even elderly people, could actually climb up to places like Lake Oesa above Lake O’Hara. The most moving thing to me was when I went on that trail up to Lake Oesa and saw the rock stairway he built, apparently single handedly. He had something in him which was not only a love for the mountains and the desire to make sure people had access to them, but also an innate sense for nature.”

Before Grassi built the trail up to Lake Oesa, Alpine Club of Canada mountain guides had put up a wooden ladder for their clients to climb in order to reach the lake. Of Grassi’s trail, Costa notes: “That alone was something that strikes directly at the heart of how generous was this man, who made it possible for average, middle-aged and even older people to go up. His (rock) stairways were perfectly built, and bear witness to the heartfelt way in which this man gave himself to the mountains – that was his approach to building trails.”

Banff’s Jon Whyte, author, broadcaster, publisher and museum curator, describes Grassi’s trail building in his book, Tommy and Lawrence – The Ways and the Trails of Lake O’Hara: ‘With wheelbarrow, prod pole, mattock, crowbar, shovel, spade and muscle, Lawrence singlehandedly made a path out of the materials at hand, heaving flat-faced rocks of a hundred kilograms or more into place …In the middle section, where the trail steepens, he lifted forty or fifty rocks that must have weighed more than he did and built wide, substantial staircases ….We may be in awe of the achievement of the pyramids; we should be in equal awe of Lawrence’s accomplishment, for on the Nile’s edge two or three hundred workers heaved a stone in the cool Egyptian winter, but Lawrence worked alone.’

Grassi’s strength was legendary, and his biographers recount that he came to be known as the “little Italian superman” of the Rockies. At one Alpine Club of Canada camp, in the Tonquin Valley in Jasper National Park, Grassi swiftly carried an injured climbing companion for more than three kms down a rocky mountainside, across a treacherous glacier and down to tree line to meet a rescue party.

Grassi went out of his way to help people. “All those who climbed with him always paid homage to his ingenuity, his strength and his generosity in helping – ‘generous’ is the one word that always comes to mind.”

During his research at the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Costa recalls reading a letter written by a man whose son had died skiing in the mountains around Lake O’Hara. The body had not been found, despite the best efforts of search parties. One day, Grassi set out by himself to look for the body of this young man, whose parents were desperate to find him in order to give him a proper burial. Grassi found the body and brought it back. “There is this very moving letter from the father to Lawrence Grassi, in the Whyte Museum in Banff,” Costa says.

Hiking guidebook author and photographer Don Beers wrote about Grassi in his trail guide, The Magic of Lake O’Hara. “He was such a wonderful gentleman. He was a great mountaineer, and very modest,” Beers recalls.

In his book, Beers describes how Grassi – like other Lake O’Hara wardens who followed him – went far beyond the regular duties of a warden. ‘A warm-hearted, modest man, not content merely to patrol the area, he was found each day, dressed in overalls, improving or building trails,’ Beers wrote of Grassi. ‘On days off he would carry firewood up to the Abbott Pass hut so that climbers would be comfortable. The heavy work he did belied his age and deceptively portly appearance. He was a man of uncommon strength, who in earlier days had carried a cast iron stove from the Highway to the Elizabeth Parker Hut.’

Grassi also built hiking trails in Banff, Skoki, Bragg Creek and Canmore, including the trail to the twin lakes that now bear his name.

There have been many legendary mountaineers, alpinists and mountain guides. Grassi was one of them, and also stands in a league of his own. His was a life of service. His focus was always on sharing his love of the mountains with others, by helping them enjoy the mountains more easily and safely.

Mount Lawrence Grassi overlooks Grassi Lakes. It is the main peak in a massif that includes Ha Ling (2,408 m), the westernmost summit; Miner’s Peak (2,338 m) and Ship’s Prow Mountain. The Stoney Nakoda also have a name for this massif – the Ehagy Nakoda Range.

Lawrence Grassi died in 1980. Yet his influence, and great passion for the mountains, endures. In their biography, Costa and Scardellato recount a story about Grassi that reveals his love for the Rockies, as recorded by Whyte in Tommy and Lawrence:

‘Major F. Longstaff, a very old-time friend of O’Hara, met Grassi on one of his last visits to the lake about 1960. He said to Grassi, “I don’t suppose I’ll be coming up here again. I’m getting a bit past it now.” To this Grassi replied, “Oh Major, hundreds of years from now, I’ll be meeting you coming round these trails.”’

If you’d like to visit Grassi Lakes, the best times are in the spring, summer and fall when the trail is snow-free. Bring ice cleats and hiking poles if there is any snow or ice. In summer, especially on long weekends, the parking lot can fill up quickly. Grassi Lakes Trail is an approximately 4 km round-trip, with 300 m in elevation gain. Seasonal conditions permitting, you can do a loop: walk up the Interpretive trail and return via the old logging road (Grassi Lakes Upper).

The trailhead, located just past the Canmore Nordic Centre, is a short drive from A Bear and Bison Inn.

Resources:

https://www.albertaparks.ca/parks/kananaskis/kananaskis-country/advisories-public-safety/trail-reports/canmore-and-area/grassi-lakes-interpretive/

https://utorontopress.com/ca/lawrence-grassi-4

Read more from Jacqueline Louie

The Dark Side of The Mountain, The History of Ha Ling Peak – A Bear and Bison Inn