February 12, 2024

Bridging the Wild: The Rise of Wildlife Overpasses in Alberta

By Jacqueline Louie

Roads are one of the biggest barriers for wildlife to move, live, and thrive.

Wildlife crossings are one solution to help landscapes stay connected, allowing animals to get from one

side of a barrier to another. Banff National Park is a world leader when it comes to animal overpasses

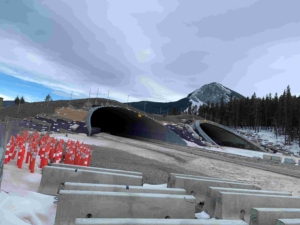

and underpasses, and now, there is a new wildlife crossing, the Stoney Nakoda Exshaw wildlife overpass,

east of Canmore at Bow Valley Gap on the Trans-Canada Highway.

“

We are really happy that Alberta and Canada are using this as a solution to improve connectivity for

wildlife,” says Kelly Zenkewich, senior communications and digital engagement manager with Y2Y, the

Yellowstone 2 Yukon Conservation Initiative, which works to connect and protect habitat from

Yellowstone to Yukon so that people and nature thrive.

Work on the Stoney Nakoda Exshaw wildlife overpass broke ground in the spring of 2022, and is

expected to be completed by late summer 2024. The province of Alberta is funding the approximately

$17.5 million project, which is being built by construction contractor PME and engineering firm Dialog

Design, working on behalf of Alberta Transportation and Economic Corridors. The wildlife overpass

project also includes the installation of 12 kilometers of wildlife fencing and 22 jump-outs — animal

escape ramps that allow wildlife stranded on the highway side of a fence to make their way back into

the forest.

Research has shown this is a preferred location for animals such as elk, deer, and grizzly and black bears

to cross the highway, and it’s not surprising this is an area with a high rate of animal-vehicle collisions.

Property damage from collisions at this location totals approximately $750,000 each year, notes Ubaid

Khan, Alberta Transportation and Economic Corridors construction manager, southern region.

This will be Alberta’s first animal overpass built outside of the national parks. (There is also an existing

animal underpass near Dead Man’s Flats). Animal crossings were first built in Banff National Park in the

1990s, to resounding success. Not only did the wildlife bridges enable animals to cross the Trans-Canada

Highway, animal-vehicle collisions went down by more than 80 per cent (and vehicle collisions with deer

and elk dropped by 96 per cent).

“These crossings are important for safety. They also have a cost-saving benefit. Injuries, insurance,

cleanup, and property damage — all of those things are limited when there’s an animal crossing,”

Zenkewich says. “The most important thing, is the overpass plus the fencing, because without the

fencing to funnel wildlife to the crossing, animals would cross anywhere. They need to know it’s there.

“Although this is only one overpass, it’s really one part of a system along Highway 1 to improve

connectivity, for wildlife and for people. We’re really excited for this project, and we’re still thinking

about other opportunities to improve connections for wildlife and people.

“These are best highway crossings for animals in the world, and now, more people around the world are

building them.”

Traditional Knowledge

“The Stoney Nakoda First Nations — comprised of the Bearspaw, Chiniki and Goodstoney First Nations

— have lived on these lands since time immemorial. They know this territory. Their knowledge was part

of pinpointing this location. And at the groundbreaking, they were there to start the project in a good

way,” says Kelly Zenkewich, senior communications and digital engagement manager with Y2Y, the

Yellowstone 2 Yukon Conservation Initiative.