March 8, 2023

Canmore’s Bald Eagle Peak: Rising above the shadow of the past

By Jacqueline Louie

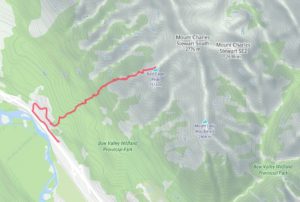

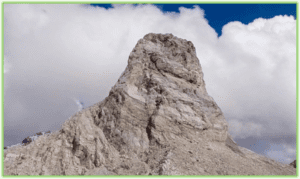

With a summit that rises 2,500 m (8,248 feet) above sea level, Bald Eagle Peak is a prominent landmark overlooking the town of Canmore. In the Stoney Nakoda language, the mountain’s name is Anû Kathâ Îpa. The peak, an outlier of the Fairholme Range, is the high point of a ridge between Mount Lady Macdonald and Mount Charles Stewart.

It was in 2020 that the name, Anû Kathâ Îpa – Bald Eagle Peak replaced an unofficial, locally used name for the peak – Squaw’s Tit. For many years, going back to the 1920s and likely even earlier, this name was associated with this mountain.

“That name was never officially recognized by any level of government, but was widely used in the area, and quite commonly used locally in the climbing and hiking community,” says Alberta Historic Places research officer and Geographical Names Program coordinator, Ron Kelland.

It may seem astonishing that this name was used for a century or more. But some people – locals and visitors alike – wanted to see it changed. It was a process, and involved individuals, as well as communities.

“There were definitely concerns about it from members of the public. Some members of the public wanted that name to be replaced by something more appropriate, more dignified and hopefully Indigenous in origin,” Kelland recounts.

People proposed alternate names: one idea, was to change it to Mother’s Mountain. Another suggestion was to remove the first word, while keeping the second word.

Geographical naming decisions are evaluated by the Alberta Geographical Names program and referred to the Alberta Historical Resources Foundation (which strongly preferred a new, Indigenous name for the mountain). Kelland explains that the Alberta Geographical Names Program had been reaching out for a number of years to the Treaty 7 Nations, hoping to learn about a traditional, Indigenous name – “something more appropriate for that mountain.” Finally, in 2020 a group of Stoney Nakoda elders held a ceremony on the slopes of the mountain and gave it the name, Anû Kathâ Îpa – Bald Eagle Peak.

The Alberta Geographical Names Program then sent letters to the other Treaty 7 nations asking their opinion of the new name. “After a period of time, we put that name forward to Alberta’s Minister of Culture and Status of Women, to be adopted as the official name for that mountain,” Kelland says. “It was really that group of Stoney elders coming forward and saying, ‘Enough of this. Here’s what we call this mountain.’ It shows the importance of having the involvement of community in that naming process.”

For Canmore Mayor Sean Krausert, the name change to Bald Eagle Peak is welcome on many levels. “The name is bestowed by the Indigenous peoples to this area, and recognition of same is one small but significant step towards reconciliation. The name change also represents a repudiation of racism and bigotry in all of its various forms,” Krausert says.

And as Bill Snow, acting director of consultation with the Stoney Tribal Administration puts it: “That colonial, misogynistic attitude has been replaced with an Indigenous interpretation and Indigenous traditional world view of that place.”

The successful outcome of the renaming process was as expected, notes Métis lawyer Lisa Weber – “but I don’t want to underestimate the effort it took to get this done.”

Reflecting on the mountain’s former, unofficial name, Weber says: “The fact that we have a place we are so proud of as Canadians, the Rockies, in such a beautiful town as Canmore where we have international visitors, and in the face of that we have a mountain that had such a misogynistic name used historically in a really derogatory manner about Indigenous women – that just flies in the face of that beauty and everything we’re proud of.

“As an Indigenous woman who has been involved in issues relating to violence against Indigenous women, girls and people for most of my career, the fact that this mountain had such a derogatory name that was accepted for so long is a very clear example of how colonization permeates into so many different aspects of our lives – and sometimes we’re not even really aware of it.

“We are now at a real pivot point in society in rectifying past wrongs,” adds Weber, who serves as president of the Institute for the Advancement of Aboriginal Women, a not-for-profit advocacy organization based in Edmonton. “Not only having the new name – it also ties back to the work of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. ‘Be a changemaker’ was one of the key messages that came out of the inquiry. Be committed. If we’re going to make changes, be a part of that.”

And, while Anû Kathâ Îpa – Bald Eagle Peak is a fitting name for a beautiful mountain, more work remains to be done in terms of geographical place names, according to Snow.

“There’s a whole list of other places that need name changes and name corrections. All of these places have stories. There are more places that need name changes, not just because they’re embarrassing to settler society, but also because they are not fully representative of the Stoney name for that place,” Snow says. “It takes a lot of research. It takes capacity and resources to do that, and right now that’s lacking on the side of the government, because it’s the government that officially names these places.

“We always struggle with understanding two world views. One world view is the view that looks at everything as objects.” For example, Snow points out, a Canadian Pacific Railway surveyor wanted to blast a hole through a prominent Banff area mountain to build a tunnel, and that mountain has been known as Tunnel Mountain ever since, even though the tunnel was never built. “The other world view is that we learn from nature, we accept gifts from nature, and we are part of a more holistic view when we understand traditional knowledge.”

Snow’s late father, Chief John Snow, describes the Stoney people’s relationship to the Rocky Mountains in his book, These Mountains Are Our Sacred Places: ‘In the olden days some of the neighbouring tribes called us the “People of the Shining Mountains.” These mountains are our temples, our sanctuaries, and our resting places. They are a place of hope, a place of vision, a place of refuge, a very special and holy place where the Great Spirit speaks with us. Therefore, these mountains are our sacred places.’

Anû Kathâ Îpa – Bald Eagle Peak is considered a moderate scramble with exposure and one harder step, according to the guidebook, Scrambles in the Canadian Rockies, by Alan Kane.

Please note: Scrambling Anû Kathâ Îpa – Bald Eagle Peak is suitable for experienced climbers and scramblers. It is not a hike, there is no trail to the summit.

Resources:

These Mountains Are Our Sacred Places – The Story of the Stoney People, by Chief John Snow

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2158358.These_Mountains_Are_Our_Sacred_Places

Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/final-report/

Read More from Jacqueline Louie